MED Magazine - Issue 46 - August 2007

Feature

From corpora to confidence

by Michael

Rundell and Sylviane Granger describe a corpus-driven research project

• The native-speaker corpus

• The learner corpus

• A joint research project

• Resources

• Goals

• Findings

• Discussion

• Solutions

Dictionary-making was revolutionised by the arrival of large language corpora in the 1980s. The use of corpus data transformed not only the process but also the product, and dictionaries designed for learners of English have improved enormously. They perform their traditional functions – explaining meanings, giving examples of usage and describing syntactic behaviour – more effectively than was previously possible. But additionally, the use of corpora has made possible more detailed and systematic coverage of phenomena such as pragmatics, register and collocation. Although lexicographers were among the earliest users of these resources, the use of corpora is increasingly common in other linguistic fields, both theoretical and applied.

Among the many insights arising from corpus linguistics, two are worth mentioning here. First, a recognition of the limitations of our own mental lexicons. Our intuitions as fluent speakers are a valuable resource when we are analysing language data, but they are not always a reliable guide to how language is actually used, and introspection alone can never underpin a satisfactory account of word meaning and word behaviour. Secondly, the study of corpus data reveals the ‘conventional’ and repetitive nature of most linguistic behaviour, and demonstrates the fundamental importance of context and co-text in the way we use and understand words. An ‘atomistic’ conception of words, as independent bearers of meaning, has given way to what John Sinclair calls ‘the idiom principle’ – a model of language which recognises that the linguistic choices we make are far from random and that a high proportion of our written and spoken output consists of semi-preconstructed chunks of language. This model of language has been very influential, not only in the design and content of learners’ dictionaries, but also in the theoretical and practical aspects of language learning and language teaching. (Michael Lewis’s ‘lexical approach’, for example, is underpinned by what corpus linguistics has taught us about the workings of language.)

In a parallel development, we have seen the creation and exploitation of a different type of corpus: the learner corpus. While a ‘standard’ corpus, like the British National Corpus or Bank of English, consists of texts written (or spoken) by native speakers, a learner corpus (LC) draws on texts produced by foreign language learners. And just as the reliability of a native-speaker corpus depends to some extent on the range of text types it includes, so a well-designed LC will source texts from learners at each main level of proficiency and from a range of mother-tongue backgrounds.

Both insights mentioned above apply equally to the study of learner data. As with native-speaker corpora, the limitations of intuition quickly become apparent: experienced teachers may have a good idea of the words or structures that their students tend to stumble over, but this can never provide more than a partial account of the problems learners face at different stages in their progress towards proficiency. At the same time, evidence from native-speaker text for the conventional character of most language events is mirrored in LC data, where many recurrent phenomena can be observed.

A thriving research community has grown up around LCs, with significant outcomes in areas such as SLA research, testing, curriculum design and teaching materials. Dictionary publishers have used LC data too, as a basis for ‘common error’ notes, like this one from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary:

This is useful enough as far as it goes, but the huge potential of LC data for improving learners’ dictionaries is still largely unrealised. A key objective of dictionaries of this type is to help language learners in their encoding activities, including of course the many learners who are required to write discursive text in academic or professional environments. And while tertiary-level texts in a native-speaker corpus provide evidence for the characteristics and conventions of this genre, it is LC data that shows exactly which aspects of the writing task learners have difficulty with.

The idea of applying insights from learner corpora to the creation of writing materials led to a two-year collaborative project involving a dictionary publisher (Macmillan) and a research institution specialising in the development and exploitation of learner corpora (the Centre for English Corpus Linguistics, Université catholique de Louvain).

The approach we used was to compare native and learner texts of the same general type in order to identify systematic differences between the two sources. It is important to stress that we were not simply looking for learner ‘errors’, but rather for evidence of significant disparities in the strategies each group used when performing particular functions in text.

The resources used were a corpus of native-speakers’ academic writing (including 15 million words from the BNC and a smaller home-made corpus of academic texts) and an extended version of the International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE), containing about 3 million words of learners’ argumentative essays. (Note that ICLE contains data from learners of 16 different mother-tongue backgrounds, including Romance, Germanic and Slavic languages, as well as Chinese and Japanese.)

An important principle in analysing corpus data is to look for language events which are both frequent and well-dispersed, occurring in many different source texts. This is what dictionary-writers are interested in describing, what teachers want to teach, and what students need to learn. The principle applies equally to the analysis of LC data: what we focus on is behaviour that is both recurrent and characteristic of learners from several mother-tongue backgrounds. The ultimate goal of our project was to develop corpus-driven materials for inclusion in a learners’ dictionary that would help learners to negotiate known areas of difficulty in their writing.

Our analysis throws up two broad areas of difficulty:

- lexical and grammatical accuracy

- fluency in writing

Looking first at accuracy, the data shows up problems in areas such as lexical choice, register, countability, the use of articles and quantifiers, and syntactic patterning (or complementation). The table below shows some typical examples of learners’ output:

| sentence from ICLE | problem area |

Although the slavery was abolished in the 19th century, black people still face racism in all parts of the world. We are a civilised society, it is true, but every year there is an ever increasing number of violence around us. |

articles, quantifiers |

| You need to balance the evidences from both sides. | countability |

Some researchers suggest to reformulate the hypothesis in more general terms. Television brings many benefits, but it can also have a bad influence to people. |

complementation |

| During the last few decades, there has been lots of discussion about the possibility of machine translation. |

register |

| University learns you how to think and judge with your own mind. | lexical choice |

Equally interesting is the issue of learners’ fluency as writers. Writing with confidence calls for a wide repertoire of words and phrases that enable the writer to express concepts and perform common functions in natural and stylistically appropriate ways. This is quite a challenge, and our analysis indicates that many learners are operating with very limited resources. Consequently, they tend to rely on a small range of devices which they use repeatedly (and sometimes misuse). Corpus-querying software makes it easy to compare wordlists from comparable corpora and identify cases where there are significant differences in frequency – where, for example, learners repeatedly use a word or phrase which is far less common in native-speaker text. In most cases, it is not a question of finding ‘errors’; the usage will often make perfect sense and conform to grammatical rules. But when we find, for example, that learners writing academic texts use the discourse-marker besides about 15 times more frequently than native speakers writing in the same mode, there is at least an issue to be discussed.

Any writer creating an argumentative text will, at some point, need to express an opinion about a contentious issue. LC data reveals a spectrum of uses among learners performing this function, ranging from the straightforwardly unacceptable to the merely inelegant. So we find plenty of evidence for expressions like this:

*According to me, the prison system is not outdated.

But there are also less clear-cut cases, such as this:

However, as far as I am concerned, there are many reasons why gun ownership should be made illegal.

Corpus data indicates that as far as I am concerned and from my point of view are both popular with learner writers, yet these expressions are barely used at all by native speakers (for whom in my opinion and in my view are far more common devices). Another gambit popular among learners is to begin a statement with I think:

I think that a sense of humour is a very important quality.

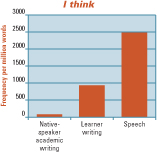

The graph here shows the relative frequency of I think in native-speaker academic writing, learners’ writing, and native-speaker spoken discourse:

Though I think is characteristic mainly of spoken language, it is clearly a popular device among learners for introducing an opinion. This could not be said to be categorically ‘wrong’, but learners’ preference for this usage is one of many instances of overuse that our analysis has uncovered. These statistical disparities call for an explanation.

Discussion

In some cases, overuse or misuse reflects an incomplete understanding

of the meaning, register features or grammatical behaviour of a word or

phrase. Consider this, for example:

* The Ministry of Education claimed that children should get more free time.

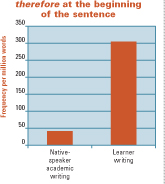

Here the writer has over-generalised, using claim (which implies that a statement is unproven and possibly wrong) instead of a more neutral reporting verb like state or argue. Colligation is another problematic area. As defined by Michael Hoey, this notion includes the ‘place in a sequence that a word or word sequence prefers (or avoids)’, and there are many cases in learner writing where an expression that carries the ‘right’ meaning is used in a non-preferred position in the sentence. A good example is therefore, which – as the graph here shows – is rarely sentence-initial in native-speaker text, but frequently used in this way by learners:

Register mismatches account for learners’ overuse of discourse markers like besides (see above) and by the way, or of expressions of modality like maybe. But the primary issue is lexical poverty: many learners are operating with a very limited repertoire, so their frequent resort to a small stock of common, general words and phrases is hardly surprising. The data shows, for example, that learners use important far more often than native writers do, while near-synonyms like key, critical and crucial are relatively infrequent in learner writing. This can often lead to vagueness, as for example when learners use thing (as they frequently do) when introducing a topic, issue, point or question that they want to discuss.

These are just a few of the things (or issues, or questions) that were uncovered through a comparison of native and learner performance in similar types of writing task.

The next part of the project focused on devising materials (for inclusion in the Macmillan English Dictionary) to help students achieve higher levels of accuracy and fluency in their writing. Accuracy entails the avoidance of grammatical, morphological, orthographic and other forms of error. It could be argued that problems of this type are so diverse that any materials aimed at pre-empting them could never be more than a drop in the ocean. However, good corpus data enables us to pinpoint those learner errors which are especially widespread and recurrent, and we believe there is value in systematically targeting these problem areas. For a range of individual errors (covering nine categories, including complementation, countability and register), we have used a model in which boxes appear at over 100 individual dictionary entries, with the following components:

- authentic examples of the error in text written by learners;

- a clear explanation of the source of the problem;

- recommended alternatives.

Here is an example:

Boxes such as these can be complemented, in an electronic version, by exercises specially designed to consolidate learners’ newly-acquired knowledge. Problems around fluency call for a different approach. Here we have focused on a number of functions that are crucial in academic and professional writing. Writers regularly need to do things such as introducing topics, drawing conclusions, paraphrasing, contrasting and quoting from sources, but our evidence shows that learners’ fluency in these areas is constrained by limited linguistic resources. Our strategy, therefore, is to provide a rich description of the words and phrases that are typically used when performing EAP functions of this type.

A typical section would deal with the function of ‘expressing personal opinions’. It is important to list and explain the various strategies that can be used when expressing an opinion, with the aim of enriching learners’ repertoire and giving them a wider range of options. For the key words and phrases, information should be provided about:

- their meanings and the nuances they carry;

- their frequency;

- their register;

- their colligational preferences (eg most usual position in the sentence);

- their collocational features;

- any common pitfalls in their use, as revealed by the data.

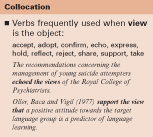

Frequency graphs like the ones above show up any major disparities between native and learner writers in the use of certain words or phrases. The aim here is to discourage ‘overuse’ and to encourage learners to try new ways of expressing familiar concepts. Once they have selected a particular strategy, learners will often need information about its preferred lexical environment, which can be supplied in collocation lists like this:

A further point is that, when providing alternatives to an overused device, one should not merely offer a set of near-synonyms. In some cases, a completely different structure may be more effective. When expressing an opinion, for example, it will sometimes be better simply to omit markers like in my opinion, so that the writer’s view emerges implicitly. In other cases, a better option may be an impersonal structure such as it is worth V-ing, where the verb slot can be filled by words like noting, pointing out, emphasising or remembering. A final option for expressing the writer’s opinion could be the use of ‘stance’ adverbs such as interestingly, surprisingly or arguably.

For every strategy suggested, a dictionary can provide enough information (whether syntactic, semantic, collocational or whatever) to enable learners to make an appropriate selection and then deploy their preferred option with confidence.

* * *

It could be argued that native-speaker data (as found in our ‘reference’ corpus) is not necessarily an appropriate benchmark by which to judge learners’ output. And for advocates of English as a Lingua Franca, the notion that learners should aspire to native-speaker models will be problematic. But on the evidence of our corpus analysis, it is clear that many learners are held back by the poverty of their lexical resources. Too often, this manifests itself in text that is depleted, unnatural, repetitive and much less effective or professional-looking than it could be. A corpus-driven approach like the one described here is a good first step in producing materials which are not intended to be ‘remedial’ but rather to give ambitious learners the information that will help them to achieve greater accuracy and fluency in their writing.

Granger S ‘Practical applications of learner corpora’ In Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, B (Ed) Practical Applications in Language and Computers (PALC 2003) Peter Lang 2004 Hoey, M Lexical Priming: a new theory of words and language Routledge 2005 Lewis, M Implementing the Lexical Approach. Putting Theory into Practice Thomson Heinle 2002 Sinclair, J Corpus, Concordance, Collocation OUP 1991 |

Michael Rundell is a director of Lexicography MasterClass Ltd and editor-in-chief of the new second edition of the Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (2007).

Sylviane Granger is director of the Centre for English Corpus Linguistics at the Université catholique de Louvain

First published in English Teaching Professional magazine www.etprofessional.com © Keyways Publishing Ltd 2007.

MED Magazine would like to thank ETP for permission to reprint this

article.

Copyright © Macmillan Publishers Limited 2007

This webzine is brought to you by Macmillan Education